Celine Orman & Reeta Metsänen

“Rights are not granted but won by a dedicated struggle waged by the people.” This was the tenor of the 7th Gathering of Freedom of Expression that took place at Bilgi University’s Dolapdere Campus, 8-10th of October. The guest of honor was the famous American linguist and activist Noam Chomsky. Prof. Richard Falk of Princeton and Hilal Elver, professor of international law from Stanford University, Prof. Turgut Tarhanli, the Dean of Bilgi’s School of Law, journalists and writers from several countries participated at the discussion, talking about the present situation in their respective countries and sharing their opinions on global issues of freedom of expression and alternatives for the future.

Some of the speakers were themselves victims or witnesses of freedom of expression violations, others representatives from Human rights organizations such as PEN and Amnesty International whom all expressed their views and experiences in order to visualize a global overview, in an effort to see clarify the source of all the problems, and what could be done to solve them.

Falk: “Neo-liberal media gives more space to neo-fascist statements.”

Prof. Falk was critical of the neo-liberal media saying that it allocates more space to neo-fascist statements. “It’s leaning far to the right according to controversial voices,” he said.

He also pointed out that although the internet provides for a pluralistic discourse, it has also become an interface of commercial exploitation.

Hrant Dink, the Turkish-Armenian journalist, killed in January 2007 because of challenging the political system in Turkey, was taken as an example of the brutal consequences of expressing critical opinions against the mainstream. Fethiye Çetin, the lawyer of Hrant Dink, explained in her speech that the lack of empathy and understanding was the main reason for his murder. People intimidated by fear and the negligence if not the obvious collusion of the police with perpetrators contributed to his murder. “Why did this happen, is a question that remains unanswered. What we can do now is to ask that question and find the answer,” she said.

During the session entitled “Quo vadis?” – In which direction should the freedom of expression progress – the audience also took part by posing questions and offering additional topics to the discussion. One of them came from representatives from the Civil Initiative Istanbul LGBTT, an association supporting gay rights, claiming that their struggle against violations also need to be discussed in the forum, since expressing yourself also comes under the question of freedom of expression. With this the ban on headscarves along with other discriminatory practices were discussed. It seemed like the gathering was facing a challenge to expand the field of discussion facing a wide range of issues concerning freedom of expression requested by numerous groups. The organizers of the gathering explained that all these questions connect to each other and are important to look at them in a single context, but in order to progress in some way there is need to focus in one aspect at the time.

‘Manufacture of consent’

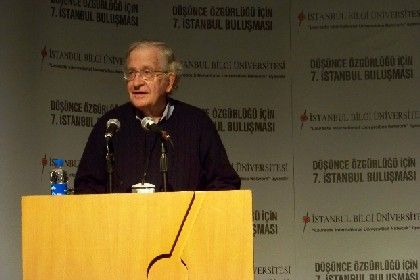

The 7th Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression culminated in the concluding speech made by Professor Noam Chomsky. The conference hall of the Dolapdere Campus was so full that to many participants disappointment, some of the audience had to follow the speech in the room next to the hall from a large screen.

In his speech “Democracy and Rights in the Emerging World Order” Chomsky addressed a wide range of issues related to the question of freedom of expression in the World and in particular Europe, United States and Turkey.

Chomsky put the issue of freedom in a historical perspective by pointing out that a century ago, “it was becoming more difficult to control the population by force. Labor unions were being formed, along with labor-based parliamentary parties and the popular movements were resisting arbitrary authority.” He went on to explain that especially in the U.S. and England, dominant sectors of the society, meaning the upper classes, became aware of the fact that they should devise new ways other than using force to control attitudes and opinions of the people.

“Prominent intellectuals called for the development of effective propaganda to impose on the vulgar masses, ‘necessary illusions’ and ‘emotionally potent oversimplifications.’ It would be necessary, they urged, to devise means of ‘manufacture of consent’ to ensure that the ‘ignorant and meddlesome outsiders’ that is the general population, be kept in their place as ‘spectators’ not ‘participants in action,’” explained Chomsky.

Public relations industry, creation of superficial demand for “fashionable consumption,” were all tools devised to keep masses of people away from policy decisions made by what Chomsky termed as an “intelligent minority.”

Democratic uprising of the ’/60s

Chomsky said that the “democratic uprising” of youth and working people frightened the ruling classes making them raise a call for an end to “excess of democracy.”

“The population must be returned to apathy and passivity, and in particular sterner measures must be imposed by the institutions responsible for “the indoctrination of the young”: the schools, universities, churches. I am quoting from the liberal internationalist end of the spectrum, those who staffed the Carter administration in the United States and their counterparts elsewhere in the industrial democracies. The right called for far harsher measures. Major efforts were soon undertaken to reduce the threat of democracy, with a certain degree of success. We are now living in that era,” said Chomsky summing up how he sees the world today.

“Turkey has a tradition of resistance”

The last part of his speech was dedicated for questions from the audience. The majority of the audience was interested in hearing Chomsky’s views on current issues in Turkish politics and society. On many occasions Chomsky modestly emphasized the fact that he is not an expert on Turkey nevertheless he had some praise for what he called the “tradition of resistance’ he sees in the people of this country.

“Turkey has its share of extremely serious human rights violations, including major crimes. But Turkey also has a remarkable tradition of resistance to these crimes. That includes, first and foremost, the victims, who refuse to submit and continue to struggle for their rights, with courage and dedication that can only inspire humility among people who enjoy privilege and security. But beyond that – and here Turkey has an unusual and perhaps unique place in the world – these struggles are joined by prominent writers, artists, journalists, publishers, academics and others, who not only protest state crimes, but go far beyond to constant acts of resistance, risking and sometimes enduring severe punishment. There is nothing like that in the West,” he said.

“There are two ways to deal with terrorist violence: either to reduce it or increase it.” Said professor Chomsky when asked what he would do if invited to take part in the Independent Commission on Turkey discussing the Kurdish question, known as the “Wise men”. “In order to reduce the violence we need to pay attention to the grievances and deal with the legitimate ones.” Professor Chomsky stated drawing examples of the developments in Northern Ireland and the Basque region in Spain. “One the other hand, violence will only increase as long as it is responded with more violence and repression.” Professor Chomsky added, with a gleam in his eye, “As you can see, this is probably why I would never be invited to such a committee”.

“Kurds should be able to use their language like it is with minority languages in other countries.” stated Chomsky when posed a question concerning the connection between language and mind. Professor Chomsky also said he was impressed by the courage of young Kurds coming up to him in a conference some years ago and presenting him with a Kurdish dictionary that is banned in Turkey.

When asked about the headscarf ban, Chomsky declared that “not allowing women to wear headscarves is a serious mistake and allowing them does not automatically mean that the Islamic law Sharia will be introduced in Turkey.” Chomsky continued his remarks by saying that similar fears of Islamization are witnesses in Europe and the United States. He added that he was especially concerned with the statement made by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel on “Germany being a Christian and Jewish country”.

In his speech professor Chomsky quoted anarchist writer Rudolf Rocker “Political rights do not originate in parliaments; they are rather forced upon them from without. And even their enactment into law has for a long time been no guarantee of their security. They do not exist because they have been legally set down on a piece of paper, but only when they have become the ingrown habit of a people, and when any attempt to impair them will meet with the violent resistance of the populace.”

“There is no point in speculation about the future. One cannot predict human affairs,” Chomsky said and concluded by a quote from Confucius: “One should keep on trying wherever the hope is.”